Consistency in Software

In an ideal world consistency in software is having one and only one way to do anything in your company, a single build pipeline, a single database technology, a single API framework, a single way to log, a single way to document, a single way to deploy…

Technical debt is often talked about in terms of old technologies, legacy codebases, monoliths and tight coupling. All these things and others are worth thinking about when it comes to technical debt, but consistency above all else should be the highest concern. At it’s core, technical debt is borrowing from tomorrow’s velocity to speed up today’s. Knowingly only changing one part of the system for some benefit, when a global update would be much more expensive is the easiest way to accrue this debt.

Adding, updating and maintaining functionality in a consistent system tends to have an linear, purely additive cost — it’s just yet another API endpoint, database call, or test case to support. Introducing inconsistency has a multiplicative cost — in the future it’s now twice as hard to understand and support two different logging platforms, monitor two different queue technologies, or remember the two code paths that create users in your system.

Inconsistency also bleeds your engineering organisation in other ways; it creates differences between teams, making it harder to move engineers around when different product opportunities arise. Production support is more complex as engineers don’t want to, or aren’t capable of, supporting systems that work differently to theirs. New work is more complicated as all the competing choices need to be evaluated to see which is the correct new best practice to copy. It promotes pockets of favouritism and emotional investment when someone’s choice eventually needs to be deprecated.

All of these downsides are forms of, or effects from, knowledge silo-ing that will also mean that you are much more susceptible to employee churn. Handovers become more critical, and more often required. It is then seen as simpler to just use something new than try to fully understand that landscape of what already exists without a guide. Knowledge gets lost and the inconsistency multiplies.

As framing it as ‘technical debt’ implies, inconsistency charges interest, but consistent software can actually be thought of as an asset, with all the benefits of compound interest. It’s much easier to take a consistent system from one consistent state to another rather than try to impose consistency on a mess competing choices. Migrating to a new database technology is easier in an organisation if you’re not using three different ones already. Both technically (tech-specific migration tooling) and organisationally (different teams might have sunk cost in their own choices). In a consistent organisation any improvements or optimisations you make will be applicable to your entire estate, and you’ll get the benefits of economies of scale. The longer you keep consistency, the more system-wide upgrades you can make at a lower cost.

While consistent systems make changing easier, they also remove choice. An odd sounding benefit, but a valuable one. There is no use in every team spending time evaluating the same decision, like which logging framework to use, when they could be writing valuable business logic. In a consistent system, whichever technology you do settle on benefits from multiple team’s investment. It becomes easy to make the right choice, it comes with so much well trodden ground it’s a no-brainer. If another option looks better for you, then it should probably be evaluated and rolled out for everyone.

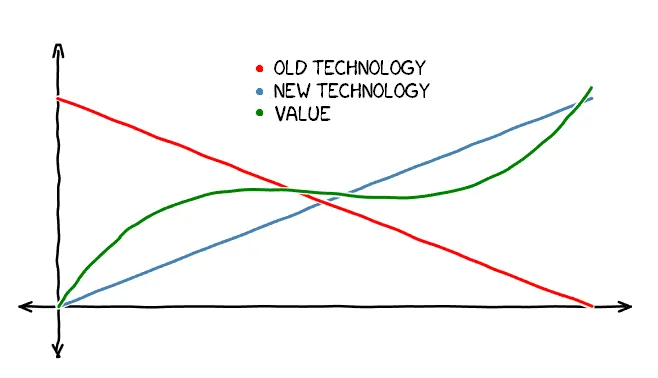

If it’s so obviously better, why do systems get inconsistent? New technologies bring large peaks of value at two stages. When they are first used and the benefits over the old technology are put to work, and when the final piece of the old technology is killed off, freeing everyone’s head-space up from it’s idiosyncrasies. Between these two peaks is potentially a long slog, involving multiple teams working together. It is much easier for an individual or a single team to access the value from the first peak — often you can introduce something new, alone. However only through collaboration can you reach the second peak, and often organisations aren’t up for that challenge.

The argument against consistency tends to be one of agility. Individual teams making choices for their benefit so they can move fast. Effectively focusing on that first peak of value. There is nothing wrong with this argument, it’s why inconsistency is technical debt. An engineering loan you can make for the short term. It however needs to be entered into like any loan; with full knowledge of the terms of the borrowing.

How do you move to have more consistency? Simply, and flippantly, just finish what you started. More seriously, almost every large scale software challenge is an organisational challenge in disguise. This challenge breaks down into three parts; decisions, follow-through and prioritisation.

Maybe architects, maybe a chapter, maybe management, but somehow force a decision making process. Decisions need to be able to be made and choices enforced and stuck to long enough to make it through to the second peak of value — consistency. This often rubs engineers up the wrong way, who feel strongly about freedom of choice and expanding their skill set. An effective counter to this is to delegate responsibility. Think about all the different individual tools, languages, frameworks that could to be consistent and hand out responsibility of each of these choices to individuals. A senior engineer can be responsible for logging and its optimisation and their work will influence every engineering team in your business. It gives people the opportunity to deepen, rather than broaden their skill sets and provides strong ownership.

The second part is follow-through. Whenever your preferred decision making process comes up with the next great thing, cost out the entire migration process and make plan that takes you all the way to consistency. Too often engineering departments fail to communicate correctly to the rest of the business the benefits of consistency and even more often fail to actually plan and pitch for consistency in the first place. It’s okay to compromise to inconsistency because the bills need to be paid, but you should aim for the full migration and know where you would spend any time you do get — a hit list of inconsistencies. Be sure to pitch this work, the second peak of value, in the name of future velocity, it’s an investment with clear, long term benefits to the company, the opposite of over-engineering indulgence.

Finally, where do you start? Look to see where you find it hardest to estimate work. Where teams are spending the most time on non-product work. What work gets the most pull-request conversations. What is hard to organise support for. Where is work slowest. What has the highest bus factor. These are many signals of friction caused by inconsistency.

A useful exercise to go through is to ask which teams is it hardest to move engineers between (within roughly similar skill sets), and keep asking why. You’ll uncover inconsistencies through the learning curve they need to go through to become an effective team member. What do you think they’ll find most confusing or difficult to adapt to, that’s probably a large source of inconsistency in your business. Likely culprits are programming language, deployment pipeline or production monitoring.

Every time you do engineering work, be it choosing frameworks, designing services or just writing code, ask yourself or your team— “Are we leaving the system in a more or less consistent state”. If the answer is less, at what point will consistency increase, do you have a plan to get there and are you all happy with the trade-off you’re making in the meantime.